1010! Challenge Part 1: Implementation and Optimisation

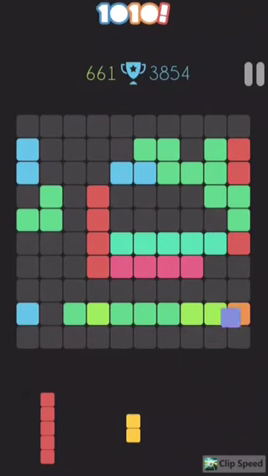

October last year, I was challenged by my wife to beat the game 1010! with AI. The score target she choosed was 50000. In the game, there is a 10x10 board and a batch of tiles to be placed on the board. One batch of tiles consists of 3 tiles. The tiles can be placed anywhere on the board, but cannot be rotated. Once a row(s) or a column(s) are full, they dissapear. The game is similar to tetris. An example play can be seen on this YouTube link.

This game has \(2^{100} = 1.27\times 10^{30}\) possible states. It has more states than Othello and Backgammon. The game tree complexities is unbounded, as one player can play the game infinitely long, if lucky. 1010! is clearly more complex than 2048, where many have made AIs to solve the game (including myself).

Implementation

I did a simple modification on the rule of the game to make the implementation of the AI easier: the tile comes one-by-one instead of in a batch of three. This makes the game harder to play, but easier to implement using tree-search, as the branching factor is reduced.

My first implementation was in Python, using binary representation of the board. As the board is 10x10, it can be represented using 128 bits: zero if blank, one otherwise.

The upper left square is represented by the least significant bit (0th bit), the square on the right of it is the first bit, the leftmost square of the 2nd row is the 10th bit, and so on.

Every tile is encoded using the bit representation, e.g. the tile with 5 squares in a row is represented by 0b11111, 2 squares in a column is 0b10000000001000000000.

If the tile is placed at some positions on the board, the tile’s bits are shifted to the left by the corresponding amount.

Checking if the tile can be placed on a certain place can be done by doing AND operation. Putting the tile on the board is done by OR operation. Removing rows and columns can be done by XOR operation.

To check the performance, I run some random plays with these steps: (1) list all valid steps, (2) choose a valid step randomly, (3) repeat from step (1) until the no valid step available. With Python, the program can run 10,000 random plays (about 180,000 steps) in about 5.2 seconds. This is not good enough as some game-playing AIs can evaluate more than million steps in a second with a single core.

Another implementation is using C++ compiled with -O3 option.

With C++, I implemented the game with standard array: the board is represented by an array of 100 boolean elements.

It consists of a lot of loops in the process: checking if the squares are blank, put a tile on the board, etc.

Initially the process seems not really efficient compared to the bit operation.

However, with the array implementation in C++, the program only needs 1.6 seconds to play 100,000 random plays (about 1,800,000 steps).

Thinking it can be further optimised, I implemented the bit operation in C++. Fortunately, my version of G++ has __int128 type for integer 128 bits.

In short, the bit-operation implementation in C++ outperforms all my other implementations: 100,000 random plays (about 1,800,000 steps) in 0.75 second.

| Language | Implementation | Plays | Time (s) | Time / plays (us) | Speed up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Python | Bit-operation | 10,000 | 5.2 | 520 | 1 |

| C++ | Array | 100,000 | 1.6 | 16 | 32.5 |

| C++ | Bit-operation | 100,000 | 0.75 | 7.5 | 69 |

I was a bit surprised to see how slow a Python script can be. With the same implementation, i.e. using bit operations, my C++ implementation runs almost 70 times faster than my implementation in Python. This is also inline with the test performed here. As a conclusion, use C++, it is fast. The codes can be found here.